My Ancient Uncle who Rode with John Brown

Charles Plummer Tidd was the youngest brother to my third great grandmother, Susan Tidd Clark

As someone who’s been fascinated by history from childhood, I’m blessed to have a rich tradition of oral family lore on both sides of my family. I’ve also got historic copies of property records, genealogy charts, and photos.

Sometimes I’ve come across unlikely family history that happened in my own backyard.

I learned from my mom that my fourth great-grandmother, Susan Tidd Clark, was a sister to Charles Plummer Tidd. He became one of John Brown’s trusted “captains.”

Susan and Charles Tidd were born to William Tidd (~1785-1865), a blacksmith, who married Elizabeth Powell in 1808 in New Brunswick, Canada. Five kids were born there before they moved to Lincoln county in southeastern Maine–about halfway between Portland and modern-day Acadia National Park.

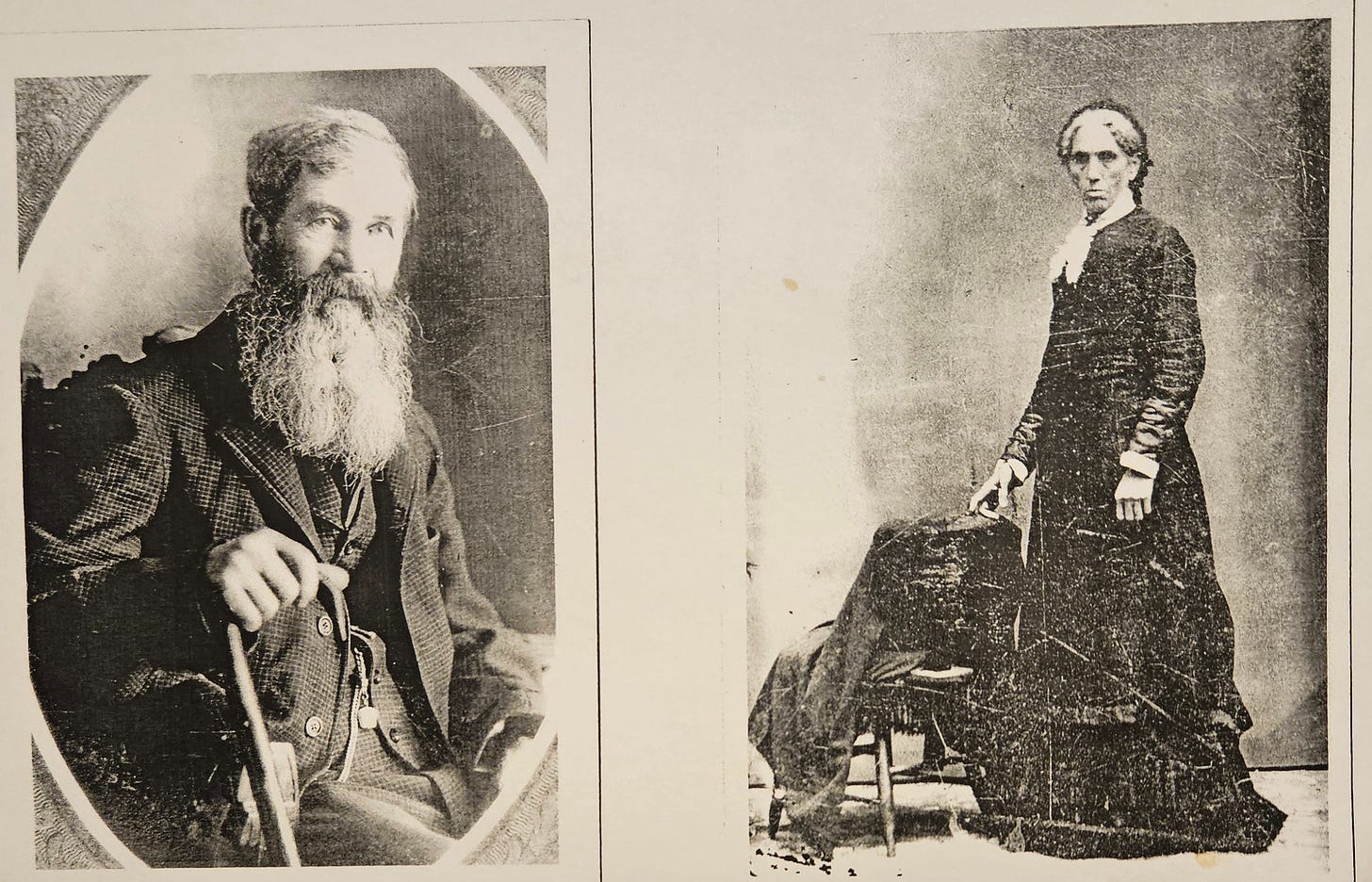

My grandmother Susan Tidd (1822-1903) married Elhanan Winchester Clark (1812-1900) in Maine. Elhanan was a fourth-generation colonist, descended from Irish immigrants. Elhanan and Susan are buried at Union Cemetery in Livermore, IA. They were among the original Kossuth county settlers in the Irvington area.

Elhanan and Susan Tidd Clark, my third great-grandparents.

Charles Plummer Tidd, born in 1834, was the 11th child born to William and Elizabeth Tidd. With a 12 year age difference, I don’t know how close my grandmother Susan may have been to Charles or what beliefs they may have shared.

Time out for a brief history review.

Leading up to the Civil War, divisions sharpened between northern free states and southern slave states. In 1821, the Missouri Compromise stipulated that slavery would be prohibited in any future states north of Missouri’s southern border. Missouri joined the US in 1821 as a slave state.

As pioneers settled in the Great Plains, hostilities erupted along the Kansas-Missouri border. Pro-slavery advocates wanted Kansas admitted to the Union as a slave state; Abolitionists strongly opposed this. “Bushwhackers” engaged in guerilla warfare during the Bloody Kansas days. Pro-Union “Jayhawkers” dispensed their own violent justice.

Charles Tidd migrated from Maine to Kansas with Dr Calvin Cutter and other free-state settlers in 1856. Sharing similar values with John Brown, he joined forces with the fiery abolitionist. Tidd helped steal back horses at Osawatomie, MO, from a pro-slavery farmer that had taken them from a free-stater in Kansas. He also helped Brown conduct a raid into Missouri to free eleven slaves, who eventually made their way to Canada.

Several sources survive describing Charles Tidd.

Annie Brown Adams wrote he “had not much education, but good common sense. He was by no means handsome…had a quick temper, but was kind-hearted. He was a fine singer with strong family affections.”

“Col Hinton” described Tidd as one of the most notable personalities in J0hn Brown’s party. “Tall, rather dark, of well-knit frame, stern and of intelligent face…a bold fighter and his companions believed he would have made a notable soldier. Fond of practical jokes…somewhat harsh in temper. A little overbearing and rude of speech, but entirely faithful and reliable. He was not attracted to the movement by any emotional or impulsive sentiment, but by a stern feeling of opposition to slavery.”

He may have been a lady’s man as well. One source tells of him writing letters to “female friends across the North” that he apparently trusted enough to share vague plans about the Harper’s Ferry raid.

According to the book Necessary Courage–Iowa’s Underground Railroad in the Struggle Against Slavery by Lowell Soike, Brown met with nine recruits at Tabor, Iowa in December, 1857. All were single men in their mid-twenties, including “short-tempered, impassioned Charles P. Tidd.”

Brown and his crew filled two wagons with Sharps rifles and headed east toward Virginia. The first journey leg took them 280 miles across the bleak, snowy Iowa prairie to the Quaker village of Springdale in Cedar county. Other than the wagon drivers, everyone walked. They arrived in Springdale nearly a month later.

Brown made arrangements t0 ship the rifles to Ohio for storage. Springdale farmer William Maxon agreed to take possession of Brown’s wagons and horses. In exchange, Maxon agreed to house Brown’s men for three months and receive $1.50 per week to cover their expenses.

Leaving his associates in Springdale for daily militia training, Brown headed to Chatham, Ontario. Fifty miles from Detroit, he attempted to recruit members of the black community to join his effort without success.

Returning to Springdale in late April, 1858, Brown learned their Harper’s Ferry plan had been leaked to a congressman. Brown had planned to raid the federal armory there, then dispense guns to slaves leading to an armed overthrow of plantations across the south.

Wanting to throw lawmen off their trail, John Brown, Charles Tidd and fellow recruit John Kagi headed to southeast Kansas.

Five antislavery settlers were massacred in that area several weeks later. Missourian Charles Hamelton and his proslavery gang had herded the men into a ravine and killed them in cold blood.

George Gill, scouting the Missouri-Kansas border for Brown, met a man named Jim Daniels in December, 1858. The “fine looking Mulatto” said he and his family were scheduled to soon be sold in an estate sale.

Brown’s men split into two groups. Brown and a dozen men liberated eight adults and two of Daniel’s children from the Harvey Hicklin farm. Another group, led by Aaron Stevens, helped “Jane,” a friend of Jim Daniels, escape. Stevens and his band also secured a wagon, provisions, oxen, and several mules. Farm owner David Cruise was killed by Stevens during the raid.

Crossing back into Kansas, Brown’s crew laid low while moving their freed quarry from place to place. On January 25, 1859, the group headed west from Lawrence to Topeka before heading north toward Iowa. A proslavery group led by John Wood surrounded them near a swollen creek, but were reluctant to fire on them. Abolitionists from Topeka arrived a few days later; Wood and his men scattered.

Four days later, the party crossed the Missouri River from Nebraska City into Iowa. They arrived at Tabor on Feb 5th. The twelve fugitive slaves huddled into a small schoolhouse. Brown, Tidd, Stevens, Gill and Kaji found refuge in homes of anti-slavery residents.

His reception in Tabor wasn’t nearly as warm as it had been a year earlier. Although Tabor’s residents were anti-slavery, many thought John Brown had gone too far. Helping already-freed slaves was one thing. But murder and conducting raids to steal someone’s “property” (whether human or horse), was something else.

After spending a week in Tabor, Brown and his party embarked on his final trip across Iowa. They stayed at the cabin of Charles and Sylvia Tolles near present-day Malvern. Describing John Brown, Charles Tolles later wrote “I did not see a savage but a determined countenance, an eye that looked straight down into your very soul.”

Brown’s entourage set out the following morning in a bitter snowstorm toward Lewis, where his cousin Oliver Mills lived. Mills worked closely with Congregational minister George Hitchcock. Brown’s gang stayed at the Hitchcock House–one of the few remaining Iowa structures surviving the Underground Railroad era.

The journey continued eastward. They spent the following two nights at the long-forgotten communities of Grove City (Cass county) and Dalmanutha (southern Guthrie county). Historical markers are posted at the ghost towns.

They spent the following night near present-day Redfield. On February 17, 1859 John Brown’s group, made up of 12 escaped slaves and Brown’s 10 men (all heavily armed) arrived at James Jordan’s farm in West Des Moines, camping in nearby timber. The Jordan House is now a museum.

Brown met the following morning at the Court Avenue bridge with long-time friend John Teesdale, owner of the anti-slavery Des Moines Citizen newspaper. Brown’s party waited nearby, the freed slaves quietly sealed in covered wagons. Teesdale paid the toll for the wagons to cross the Des Moines river.

On Feb 18, 1859, the group passed within about a mile of where I now live. They reached Brian Hawley’s farm near present day Pleasant Hill. Hawley was a 49 year old saw mill owner and carpenter. He lived just west of Yellow Banks Park, a Polk County Conservation site. I’ve camped there dozens of times.

They next stayed in eastern Jasper county at the site of a current Interstate 80 rest area, then continued to Grinnell.

Brown redesigned his delayed plan to raid the Harper’s Ferry arsenal while meeting with town founder Josiah Grinnell. After spending two days there, townspeople gave the travelers $25 and several days of provisions. They camped the following night near Marengo before arriving in Iowa City.

Not quite the liberal bastion it is today, the former state capital was sharply divided on the issue of slavery. However, they passed through Iowa City without incident and traveled fifteen more miles east to Springdale.

Brown doubled back to Iowa City, making arrangements for delivery of an empty boxcar to West Liberty two weeks later. The railroad only extended west to Iowa City at the time.

Brown sold his horses and a wagon in Springdale. Men trained and played cards while awaiting the next step.

On March 9, 1859, John Brown and his company of twelve escaped slaves and his four c0mpartiots arrived in West Liberty, an abolitionist Presbyterian settlement. They camped at Keith’s Mill overnight.

Early the following morning, a boxcar was delivered by an east-bound train as planned. As townspeople watched, Brown’s men escorted the slaves and materials onto the railcar. After loading everything else, John Brown, Charles Tidd, and Aaron Stevens boarded the boxcar before it was closed and locked. They awaited the next train from Iowa City, east-bound to Chicago. Two other members of Brown’s posse boarded the passenger car after the train arrived.

Late that night, they reached the Chicago rail yards. Private detective Allen Pinkerton and his black friend John Jones provided overnight accommodations. Pinkerton also arranged for a Michigan Central Railroad

boxcar to be loaded with provisions for the group.

Brown’s party boarded the railcar, bound for Detroit. The 1100 mile journey ended at the Detroit ferry landing, as Brown and his men bid farewell to the twelve freed slaves. They crossed the narrows to Windsor, Ontario. Truly free at last in Canada.

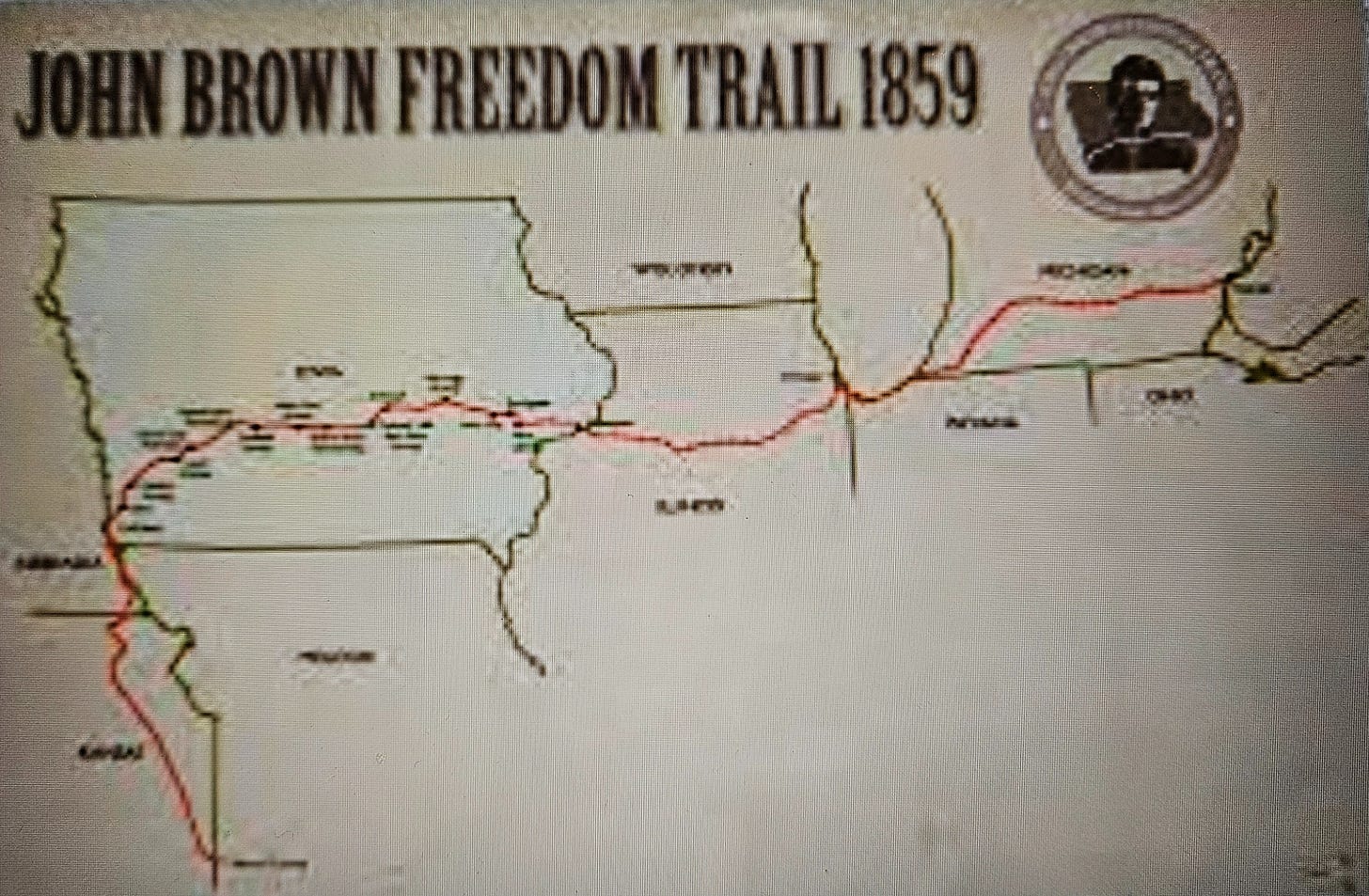

John Brown’s 1859 Freedom Trail stretched 1100 miles from SW Kansas to Detroit

Brown’s associate, John Kagi, then began recruiting men for their upcoming Virginia raid. At the time, only Charles Tidd, Aaron Stevens, and Harpers Ferry schoolteacher John Cook were the only men ready to go.

That summer, John Brown leased “the small Kennedy farm” along the Maryland side of the Potomac River. Downstream from Harpers Ferry, it served as his staging area. Sharps rifles and revolvers that had been stored in Ohio soon arrived. By August, twenty recruits had been assembled. The party included three of Brown’s sons and five black men.

Brown’s men assumed they would carry out a surprise raid on the federal armory in Harpers Ferry, grab weapons, then quickly retreat.

But in mid-October, Brown announced plans to occupy the armory until slaves, armed with weapons Brown had transported, had time to join the fight. Brown’s three sons and Charles Tidd strongly objected to that plan.

On Sunday night, October 16, 1859, Brown and all but three of his men captured the armory. Brown refused to evacuate. Local militias and citizens soon had them trapped.

The disastrous mission ended two days later. Ten men–including Oliver and Watson Brown–were killed. John Brown and four others were captured immediately; two others were arrested soon after.

Brown was found guilty of murder, inciting slaves to rebel, and treason. The night before his execution, he wrote: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land can never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed, it might be done.”

His words proved prophetic at Fort Sumter fifteen months later.

John Brown was hanged on December 2, 1859. Six of his men met the same fate.

But what became of Charles Plummer Tidd?

Charles Plummer Tidd

Shortly before the raid, he wrote to his parents. “The next time you hear from me will probably be through the public posts. If we succeed the world will call us heroes; if we fail we shall hang between the Heavens and the earth.”

Tidd and John Cook had been instructed to cut telegraph wires prior to the raid. Following that, the two men joined four others to kidnap Lewis Washington, George Washington’s grand nephew. They freed several of his slaves.

On the morning of October 17, Brown then ordered Tidd and others to capture another slaveholder named Byrne, taking him and his slaves to Kennedy farm. He did so, then transferred firearms to an old schoolhouse closer to Harpers Ferry.

Returning to the farm, Tidd learned Brown was in dire straits at the armory. Tidd and four others decided to escape before being captured, eventually making their way to central Pennsylvania in late November.

The group split up and Charles Plummer Tidd headed to Chatham, Ontario, just east of Detroit.

Dropping his last name and laying low, Charles Plummer eventually made his way to Massachusetts. He enlisted in Company K of the 21st Massachusetts Infantry Regiment on July 19,1861. He became a 1st Sergeant in November.

That winter, the 21st received orders to join operations at Roanoke Island, NC, conducted by Gen Ambrose Burnside.

Shortly after arriving near Roanoke on the ship Northerner, Plummer died of either typhoid fever or enteritis (a bowel inflammation) on Feb 7, 1862.

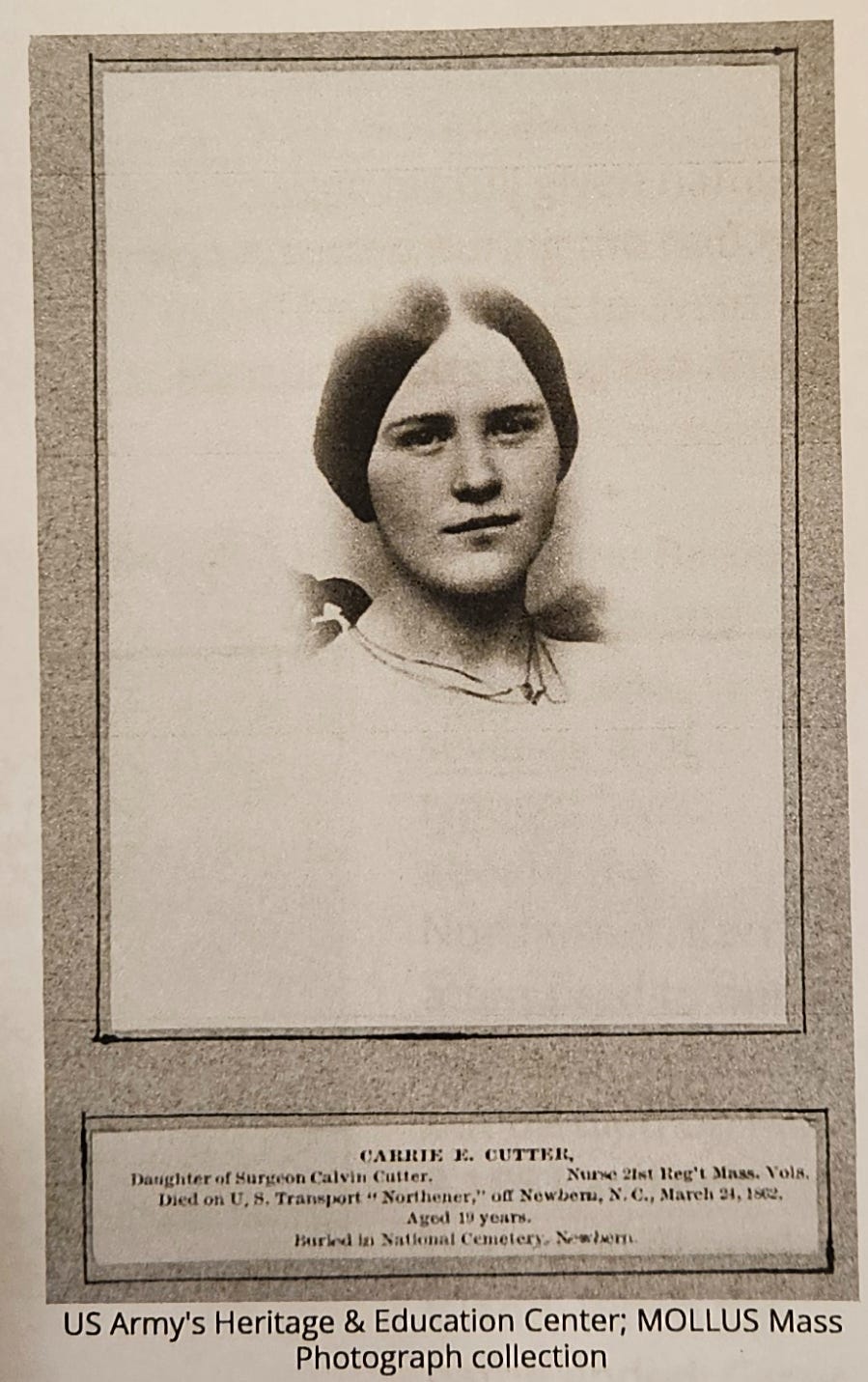

Charles Plummer Tidd had been attended to by Dr Calvin Cutter, who had traveled from New England to Kansas with Tidd six years earlier. His daughter and regimental nurse, Carrie Cutter, had also cared for Tidd.

She died herself on March 24 of spotted fever. General Burnside ordered her to be buried with full military honors.

Carrie and Charles may have been engaged. One source described Plummer as “Carrie’s sweetheart.”

The nineteen year old nurse had requested to be buried next to Tidd. Carrie Cutter is interred at the New Bern National Cemetery. A grave nearby is marked “Charles Coledge.” This may actually be Charles Plummer Tidd, his identity changed to prevent vandalism in the North Carolina graveyard.

One of the first women to die in the Civil War, the heroic Carrie Cutter was later honored in a poem by famous nurse Clara Barton.

Carrie’s stepmother, Eunice Cutter, thought highly of Charles Tidd. She had known him since the Bloody Kansas days. In an 1888 veteran’s reunion, she said “Sergeant Tidd dared to do right as he understood his Bible, dared to be true to his convictions, ‘to loose the bands of wickedness, to undo heavy burdens, and to let the oppressed to free;’ his ardent zeal often led him into peril.”

It’s inspiring to know I share blood with a man so passionate about abolishing slavery. And not only did he risk his life in rescuing the oppressed, but ultimately lost it during the Civil War.

I hope to draw faith and bravery from his life story in these challenging days. Rest easy, uncle.

Anybody else have ancestral inspiration you’re drawing from?

SOURCES:

Grover family archives

The Fighting Farmer–John Brown and Iowa, 1855-1859, by Steven Ray Davis

Necessary Courage–Iowa’s Underground Railroad in the Struggle Against Slavery by Lowell Soike, University of Iowa Press, 2013

https://randomthoughtsonhistory.blogspot.com/2018/08/searching-in-vain-for-charles-plummer.html

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/156388199/charles-plummer-tidd

https://www.susanhigginbotham.com/posts/a-memorial-day-tribute-to-charles-p-tidd-and-carrie-cutter/

https://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/19467

https://www.digitalcommonwealth.org/search/commonwealth:dz011971g?view=commonwealth%3Adz0119731

https://www2.iath.virginia.edu/jbrown/men.html

https://newbernhistorical.org/this-month-in-new-bern-history-march-2022/ poem by Clara Barton, Cutter one of 1st women to die in CW

https://itoldya420.getarchive.net/media/charles-plummer-tidd-f35cfc public domain engraving

https://iowaculture.medium.com/freedom-trail-62afa1c94b83 john brown crossing iowa

https://littlevillagemag.com/bright-radical-star-when-john-brown-came-to-iowa/

Iowa History Daily: October 16 - Iowa's Ties to John Brown & Harper's Ferry

https://abolitionist-john-brown.blogspot.com/2011/04/overlooked-chapter-john-brown-iowa-and.html

Thank you for a very fine and poignant reflection upon your ancestor and the John Brown story. I am a biographer and student of Brown's letters. My podcast is John Brown Today. When things clear up for me this spring, I'd like to do a chat with you. Regards, Louis A. DeCaro Jr.